- Researchers at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California have tested a “slow delivery, escalating dose” vaccination schedule of HIV antigen so that the immune system learns to attack it.

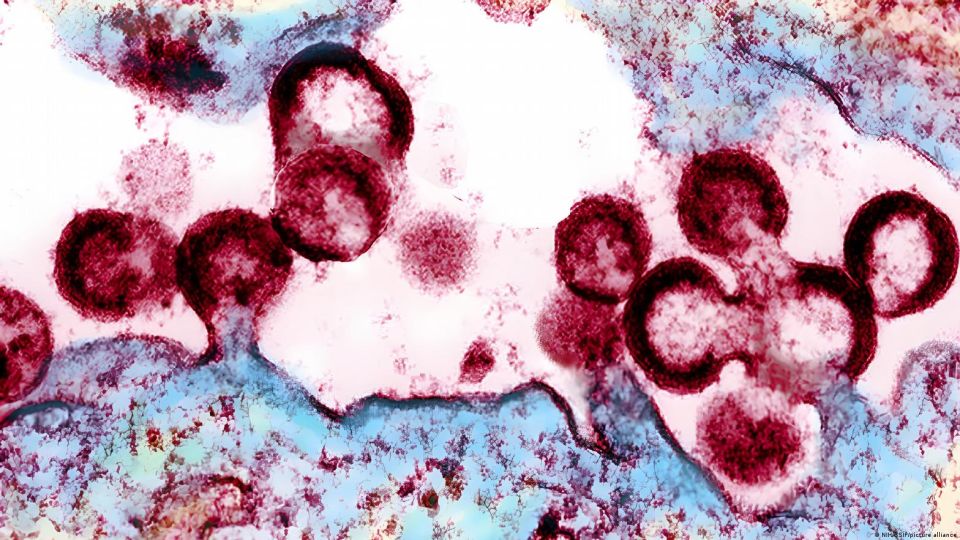

A team of researchers from the La Jolla Institute of Immunology (LJI), in California, has discovered how the immune system becomes an antibody-making machine, capable of neutralizing one of the most elusive viruses that exist: HIV.

Researchers once thought that B cells (which make antibodies) spent weeks perfecting their weapons against viral threats, but new research shows that a “slow delivery, escalating dose” vaccination strategy can cause these cells to spend months mutating and improving their antibodies against the pathogen.

This finding, published this Wednesday in the journal Nature, is an important step towards the development of effective and long-lasting vaccines against pathogens such as HIV, influenza, malaria and SARS-CoV-2.

Study Suggests Patience is a Virtue When Vaccinating against HIV

Vaccination strategy that prompts B cells to evolve over months could enable development of long-lasting vaccines against #HIV, #malaria, and #SARSCoV2. Learn more: https://t.co/MSbxzTKYoK pic.twitter.com/HyXF4ANT3q

— Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News (@GENbio) September 22, 2022

“This shows that the immune system can do really extraordinary things given the chance, and that in some contexts, patience really is a virtue,” said study lead author Shane Crotty of LJI.

Pathogens that attack the body are covered in unknown proteins, and when the body’s dendritic cells see them, they signal the T cells to start building an army.

The B cells receive the warning that an invader is nearby and the molecular marker (or antigen) to recognize it, and they start making antibodies in structures called “germinal centers”, where the B cells mutate and test their antibodies.

Those that do not mutate over time and do not improve their antibodies are eliminated and B cells with useful mutations are sent to the body for war.

The vaccination strategy

The new study highlights the importance of lengthening the period in which B cells can evolve in the germinal centers.

For the research, collaborators at the Tulane National Primate Research Center vaccinated rhesus monkeys every other day for 12 days with a series of seven injections containing an “increasing dose” of HIV antigen (the protein they wanted the immune system to detect). learned to attack).

One group of monkeys was not vaccinated again, but two other groups received a booster shot at 10 weeks, and the researchers then followed the monkeys’ immune responses.

The team also monitored the development of B cells in individual germinal centers.

The work revealed that germinal centers remained active and B cells continued to evolve six months after the initial series of seven injections.

But how did the highly evolved B cells behave?

The scientists found that monkeys given the series of seven injections and not given a booster dose had a stable and long-lasting population of HIV antibodies six months after treatment.

These animals also had more immune cells (helper T cells) ready to recognize the HIV antigen and launch B cells into battle, while the boosted animals had a second “spike” in antibody numbers after their booster injection , but they didn’t end up with the same high-quality antibodies.

The strategy of slow administration and staggered dosing had paid off.

The team is now studying whether they can achieve the same quality of antibodies with two vaccines versus seven, and also whether they can design an mRNA vaccine that causes the same evolution of B cells by slowly producing antigen over time.