The protagonist of “Diario de Rosario”, the novel by Paloma Fabrykant, works filming “shock” police forces and is attracted to these men. Daughter of “progressive” exiles, do her choices have to do with reacting to the family?

Some time ago, in an interview, the writer Leo Oyola (author of Kryptonita, Chamamé, Ultra/Tumba, among other books) commented that he used to say that he wrote detective fiction, but once someone corrected him and told him that what he actually wrote was “crime” fiction. Why? Because his stories were always on the side of the criminals, he told from that perspective and appropriated that worldview. A distinction that is not at all subtle and at the same time fundamental to think about the corner of the world from where the world is seen.

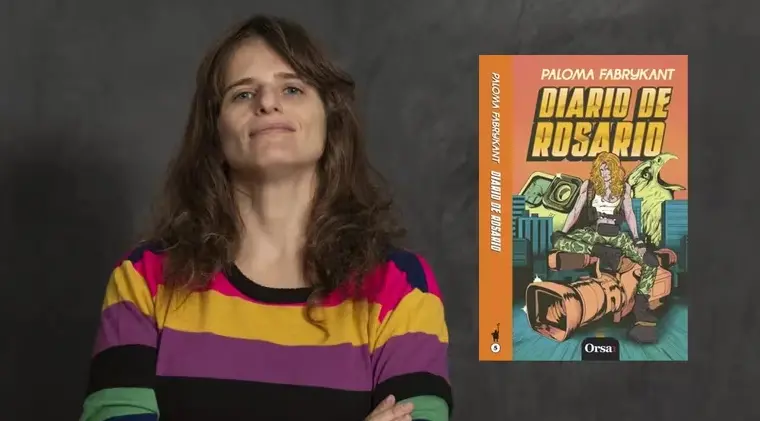

It is in this distinction between the police and the delinquent (without defining one or the other, at least at the beginning) that Diario de Rosario, the novel by Paloma Fabrykant published by Orsai, slides in a diffuse way.

The story begins with drugs (cocaine), a trip (to the Rosario of the title which is a burning point in this sense) and a protagonist who works as a cameraman and is always ready to be in the front line of battle and film for a production company (La Parrilla) the police work of shock in sectors that we could call “marginal”. And so it goes on throughout the text.

In this sense, the novel shows its cards from the first line and never abandons it: street slang (reality effect, as the French theorist Roland Barthes would say), the bet is on a specific type of action (the violence of the margins: drug trafficking, murders, consumption as a way of life, sexuality as a point of escape, raids as an adrenaline amusement park, etc.) and no moment that indicates to put an end to the violence of the margins, and no moment that indicates to put an end to the violence of the margins (the violence of the margins). ) and no moment that indicates to put a brake because the plan seems to be that in front of the facts (of this self-perceived extreme fiction) one can only react and never contemplate or reflect.

The novel manages all the time that climate of exacerbated virility to which the narrator constantly wants to reach: “Narcocriminalidad was my personal bowling alley, where I had more cattle than at a birthday party at home. There was a chubby guy I would never have looked at on the street, but when I saw him spreading his legs apart on the floor I went crazy. There was another one who, in the middle of a mess, when a lot of people came at us, stuck to me and, pretending to be a jerk, began to caress my inner thigh with the tip of his shotgun. Another hawk, after Roca, I was going to wait for him at the base. He said he would run out and get into my car. I would bring him back all sweaty,” he writes on p. 63.

Following the Police, gaining their trust, interacting with the Force in all possible ways (from distant camaraderie to the most desired intimacy), knowing it from all angles leads to think of a story that has only one ideological nuance (clearly the right wing and its imaginary of security, repression, etc.), but the narrator often explains why she chooses that world: “My parents did not want me to come, neither did my sisters. They’ve wanted me to quit this job for years. But if I don’t do this, what am I going to do? I’ve tried a thousand things and nothing fulfills me. Sitting in an office I wither away. When I tried to work in the Prosecutor’s Office it was a disaster. At least with the Police I found a place where some of my skills are valued, the more rustic ones but no less useful for that”. Was it just about having a good job after all?

“My mom doesn’t get it, she’s superzurd. My dad and I went into exile during the dictatorship because they were Peronist militants. A few years later they came back, but she never gave up on her ideals. My old lady’s hatred of the yuta is not an automatic prejudice of a bourgeois progre; it is a real fear of the people who wanted to kidnap her. How could I not understand her. She raised me in that way of thinking, but I dedicated my life to fight against her. First with martial arts (she wanted me to be a writer, not a fighter), then by dedicating myself to something frivolous like television. Working for the cana is the final blow. I don’t know why I do this to her.”

What seems like a novel that tries to scare off the “bourgeois progre” and his automatic hatred of the Police unveils its true essence: a protagonist who seeks her way in symbolic violence against everything her parents have on an altar. This leads to the following questions: in order to enter one’s own life, does one have to face the law of one’s parents? Is there an existence of one’s own without patricide?

Perhaps the essence of the novel -the magma masked and covered with all that violence with which this story chokes at times- is not really about cops and robbers (or legality vs. illegality), but about the topics that abound in any quiet after-dinner conversation where a mate circulates: the bond between fathers/mothers and daughters.

Who is Paloma Fabrykant?

♦ She was born in Buenos Aires, in 1981.

♦ She worked in journalism, advertising and TV scriptwriting.

♦ She is the author of Cómo ser madre de una hija adolescente (written by a teenage daughter) and MMA. Mixed Martial Arts.

♦ Practiced combat sports and participated professionally in vale todo fights.

♦ Covered police operations linked to drug trafficking.