April 30 (Globe Live Media)- On August 19, 1989, the newspaper ‘El País‘ published the news: “The National Heritage has informed the judicial authorities of the disappearance of three small paintings, two by Diego de Velázquez and another attributed to Juan Carreño de Miranda, valued at 275 million pesetas, which were kept in the Royal Palace of Madrid, in an area closed to the public,” the newspaper described.

Days later, the newspaper ‘ABC‘ offered more details: “In the Palace everyone is suspicious; the alarms have not sounded and the detection system did not register anything. The thieves would have moved around the Palace as if they were at home,” said a person responsible for National Heritage at the time.

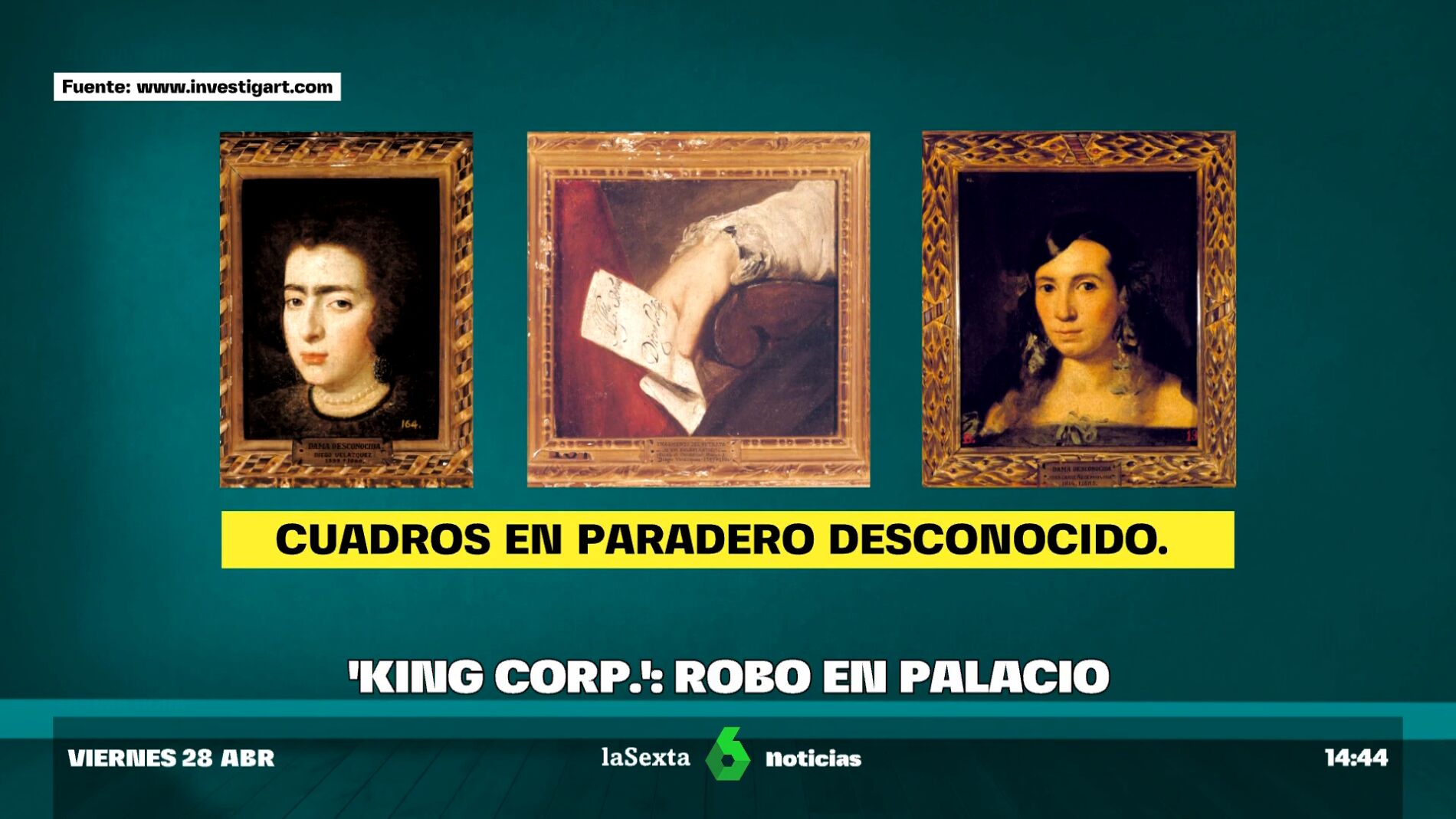

The National Police, who described the theft as curious, are still investigating the whereabouts of these three paintings: two Velázquez works, a Head of a Lady and a Hand from the portrait of Archbishop Fernando Valdés (fragment of a lost composition), and a Bust of a Lady from the time of Carlos II by Juan Carreño de Miranda, according to Gloria Martínez Leiva, PhD in Art History from the UCM and founding director of InvestigArt.

And 34 years later, the book ‘King Corp’, written by José María Olmo and David Fernández, reveals where two of those paintings might be. The book claims that the former head of state’s right-hand man at that time, Sabino Fernandez Campo, told a close friend before his death that he had seen two of the stolen paintings decorating the wall of one of Juan Carlos I’s mistresses. This was revealed by José María Olmo, co-author of the book that includes surprising chapters on the life of the father of the current monarch, Juan Carlos I.

Another curious topic related to the former monarch has to do with watches. “Juan Carlos is a watch addict; he likes them a lot, and many people gave him watches as gifts. The ones he didn’t like he would take to a trusted jewelry store and turn them into money. He sold them to, among other things, be able to buy gifts for his mistresses,” says the other author of the book, David Fernández.

These watches should have become part of the National Heritage catalog, but the king emeritus did not see it that way. According to the book, he thought that the watches were part of his retribution for his performance as king, and that is why he never reported receiving them as gifts.