- There was a time when Iranian women could go out on the streets without veils and wearing more liberal clothes, such as miniskirts or shorts. Many also decided to cover up and dress more conservatively.

“I saw many photos of my grandmother from before the revolution, her with the veil and my mother with a miniskirt, living in harmony, side by side.”

What Rana Rahimpour, an Iranian-British presenter on the BBC’s Persian service, remembers is not just confined to her family.

In Iran, before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, there was no strict dress code that currently requires women, by law, to wear the veil and modest “Islamic” clothing.

“Iran was a liberal country. Women were allowed to wear whatever they wanted,” she recounts.

Her testimony is relevant while protests are taking place in dozens of Iranian cities over the recent death of a 22-year-old girl who had been detained by “the morality police”, which is responsible for enforcing Islamic dress codes. .

Rahimpour was born after the revolution, but the experience of her parents and relatives and her journalistic work have allowed her to delve into the transformation that her country experienced after the fall of the Shah.

A transformation that, in the early years, went beyond clothing, as the Iranian journalist Feranak Amidi, a reporter for Women’s Affairs for the Near East region of the BBC World Service.

“We had no gender segregation before the revolution. But after 1979, schools were segregated and unrelated men and women were arrested if they were caught socializing with each other.”

“When I was a teenager in Iran, the morality police arrested me for being in a pizzeria with a group of friends.”

“Before 1979, there were nightclubs and entertainment venues and people were free to socialize however they wanted.”

Pre-revolution films are also testament to a time when women could choose whether to wear Western or more conservative attire.

“You saw a variety of dress styles. Some wore the black veil or chador, but not in the way that the government currently requires.”

A dynasty

Before the 1979 revolution, Iran was ruled by the Pahlavi dynasty, which began after a coup.

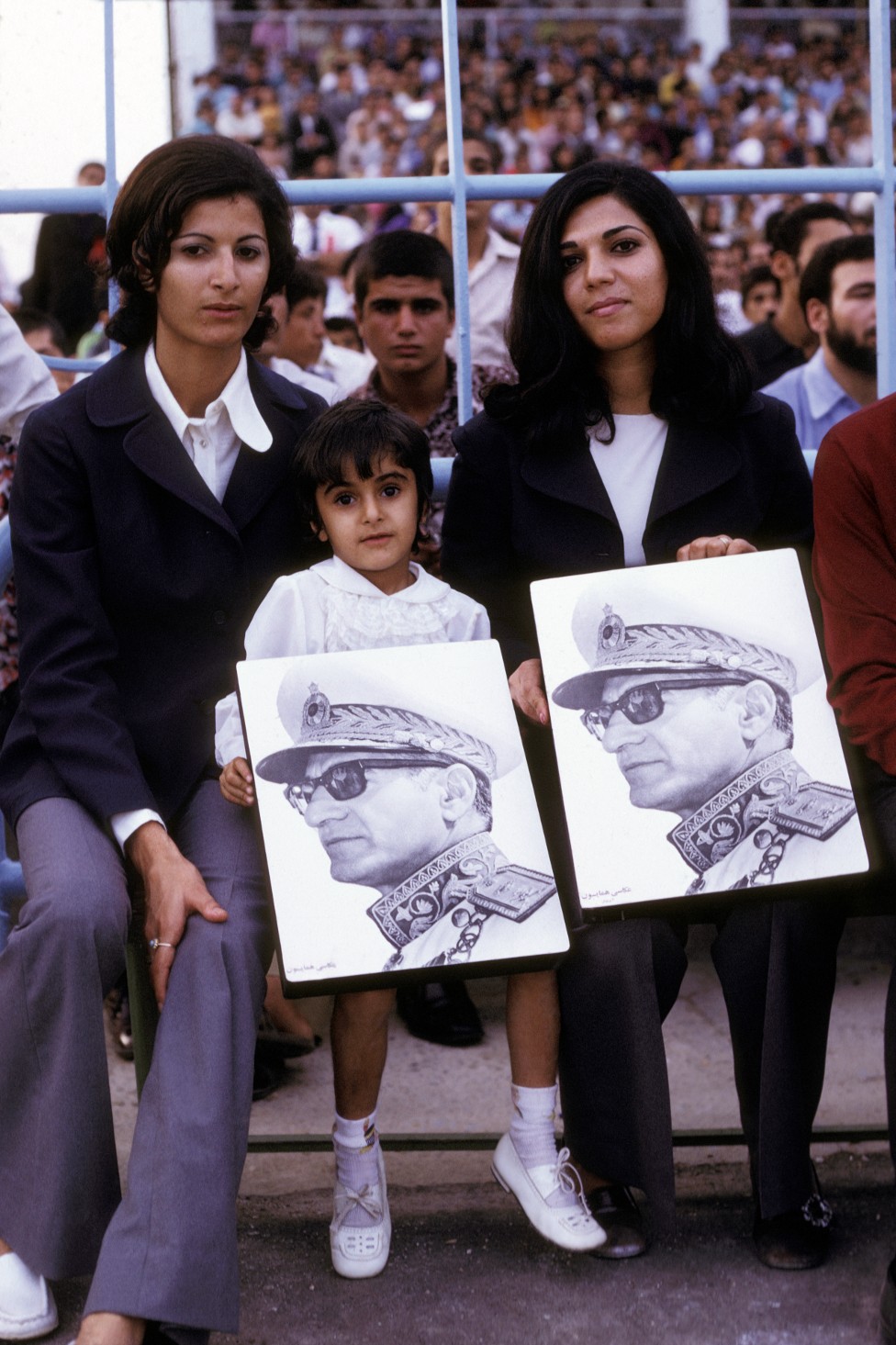

Attendees at the Shah of Iran’s birthday celebration at Abadan Stadium in the 1970s.

In 1926, the coup leader, Reza Khan, was crowned Reza Shah Pahlavi and his son Mohamed Reza Pahlavi was proclaimed crown prince. Later, he would become the last Sha. In a 1997 article, the Wilson Center think tank reproduced an interview from its Dialogue radio show with Haleh Esfandiari, author of Reconstructed Lives: Women and Iran’s Islamic Revolution. ).

Esfandiari left Iran in 1978 and returned 14 years later to investigate the revolution’s impact on women.

In that interview, the journalist told her that “the women’s movement in Iran began at the end of the 19th century, when women took to the streets during the constitutional revolution.” After that, many of them started social projects like opening schools for girls and publishing women’s magazines. Other provinces were linked to this network, which began in the capital, Tehran, and this led “to the development of the women’s movement.”

The veil

Women’s clothing had already been an issue on the agenda of the country’s leadership at the beginning of the 20th century.

Choreography in the framework of the shah’s birthday celebrations in the 70s.

“The headscarf was not officially abolished in Iran until 1936, during the era of Reza Shah Pahlavi, the father of modern Iran,” the author noted. Years earlier, the leader had encouraged women not to wear the veil in public or “to wear a headscarf instead of the traditional long veil.”

“When the veil was finally officially abolished, it was certainly a victory for women, but also a tragedy, because the right to choose was taken away from them, just as it was during the Islamic Republic when the veil was officially reintroduced in 1979.” Many women “were forced to abandon the veil and go out into the streets feeling humiliated and exposed.” Still, Esfandiari acknowledges that the father of the last shah undertook some changes that had a positive impact on women.

The White Revolution

In 1941, his son, Mohamed Reza, assumed power.

During that reign, “the modernization of the country began,” says Amidi. That process became known as the White Revolution and gave women the right to vote in 1963 and the same political rights as men. In addition, efforts were made to improve access to education in outlying provinces. In his reign, the family protection law was passed that dealt with different areas, including marriage and divorce. The legislation, Amidi explains, expanded women’s rights.

“The Family Protection Law raised the minimum age of marriage for girls from 13 to 18, and also gave women more leverage to seek divorce.”

It also limited that men could only have one wife.

“This was all quite progressive compared to other countries in the region.”

And it is that the Shah, although an autocrat, was a progressive leader and liked Western culture.

Thus, he established a program of secularization.

A street in Tehran on July 23, 1964.

Day to Day

Women came to occupy positions of power. “We had women ministers, judges,” Rahimpour recalls.

However, despite the promises of the White Revolution, “women were still confined to traditional roles,” says Amidi.

And although she highlights that “there were women in Parliament”, she considers that “women did not have a great participation in the political sphere.

But we have to keep in mind that that was almost half a century ago and women all over the world at that time didn’t have much political power.”

Even so, she recognizes that her compatriots were beginning to play an increasingly social role: “They had a vibrant presence in society.”

Women’s concern

Amidi highlights “the great impact” that Queen Farah Pahlavi, wife of Mohamed Reza, had on the arts and culture.

Indeed, an essay by Maryam Ekhtiar and Julia Rooney of the Islamic Art department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York addresses “the artistic flourishing in Iran,” which began in the 1950s and continued into the 1960s and 1970s.

“These decades saw the opening of Iran to the international art scene.”

Much of this growing artistic activity was due to the economic prosperity that the country was experiencing.

And it is that Iran had a lot of oil, but the vast majority of Iranians were not benefiting from that wealth.

Despite the support of the Shah and his wife in the field of the arts, the artists were not blind to this reality, nor to the regime’s repression against those who opposed it.

Nahid Hagigat, the authors point out, “was one of the few artists who expressed the concerns of women during the years before the revolution.”

“In her prints, she captured the feeling of tension and fear in a male-dominated society under government scrutiny.”

Elbow to elbow

By 1971, Mohammad Reza, who had declared himself “shahanshah”, “the King of Kings”, was not only one of the richest men in the world but the absolute leader of Iran.

His regime was increasingly repressive against political dissidents.

“In the regime before (the revolution) people had social freedoms, but zero political freedoms”, Rahimpour evokes.

“That was a big problem. All the parties were controlled by the king, it was a guarded society, there was no freedom of the press, any type of political activism could end up in prison”. Social discontent took to the streets and in 1978 there were massive protests against the Shah’s regime.

According to Esfandiari, the progress made by women during his reign destabilized towards the end.

“In reaction to the increasingly vocal traditionalist elements in society, the Shah drastically withdrew his support for greater participation of women in decision-making positions.” The Islamic Revolution was supported by many Iranians who “were not necessarily religious,” Rahimpour explains. Many only claimed a “true democracy.”

“He had the support of all groups, with the liberals, the communists and the religious.”

Women, regardless of what they wanted to wear or their degree of religiosity, were part of that force that ended up causing the fall of the Shah in 1979.

“In the marches that led to the revolution, there were professional women without headscarves and women of conservative origin with the traditional black veil; there were women from lower and middle class families with their children. All these women walked shoulder to shoulder, hoping that the revolution would bring them an improvement in their economic status and an improvement in their social status. And above all, an improvement in their legal status”, recalled Esfandiari.

Different Visions

Amidi does not believe that women “necessarily felt more independent” before the Islamic Revolution.

“Iran was still a very conservative religious society. But back then there was political will to break that traditional and conservative mold, and allow women to flourish and occupy more spaces in society.”

This flourishing, she clarifies, never fully came to pass. According to Rahimpour, there are conflicting ideas about whether women felt more independent and empowered before the Islamic Revolution.

“Religious women would say they felt more comfortable going out after the revolution, but liberal women would disagree with them.”

“You must not forget that there is a part of Iranian society that is very religious.” Hence, there are women who agree with aspects of the system.

Seeing archive photos of women in Iran wearing western clothes and without veils, an Iranian lady pointed out to me that these images are not representative of women’s life in general before the revolution. Many women, of different ages, chose to wear the hijab or headscarf and more conservative clothing because “society was possibly much more conservative and religious compared to today.”

Protests

Many Iranians entered the revolution hoping for freedom, but, says Rahimpour, their illusions were quickly dashed.

“After the revolution, we realized that many religious people were uncomfortable with miniskirts and with the freedoms that men and women had, and that’s why they also agreed with the revolution.” However, he says that many people who are “deeply religious” in Iran think that wearing the veil “has to be a choice.”

“It ceases to be a religion when it is forced.”

Iran is experiencing an outbreak of protests across the country after the death, in police custody, of a 22-year-old woman for allegedly not abiding by hijab rules. Authorities say Mahsa Amini died of underlying health reasons, but her family and many Iranians believe she died after being beaten.

The protests appear to be the most serious challenge Iran’s leaders have faced in recent years. And a new chapter of popular mobilizations in Iran.