With a narrower-than-expected victory, Modi secures a third term in India after a decade of popularity and polarization

Ten years after he became prime minister, Narendra Modi declared himself the winner of India’s elections on Tuesday, albeit with a narrower-than-expected victory that will force him to rely on his political allies.

With counting still underway, the Modi-led alliance of parties reached the 272-seat threshold needed to form a government.

But the prime minister’s Hindu nationalist BJP Hindu nationalist party lost its absolute parliamentary majority and is expected to end the election with 240 of the existing 543 seats, far fewer than the 400-seat target it set for itself during the election campaign.

The INDIA opposition coalition has performed much better than expected, winning 193 seats so far across the country, with a particularly strong showing in the south.

Preliminary results of this election, which kicked off on April 19 and ran until June 1, give Modi a third term in office in which he will have to rely on his allies.

But how did Modi manage to become the most popular leader India has had in decades?

In Modi’s constituency, located within the northeastern Indian city of Varanasi, Shiv Johri Patel makes a living weaving sari, a traditional Indian dress.

He admits he has many concerns, but adds that he had long been clear about who he would give his vote to.

“Modi has done a great job. Under no other government did the poor get so many social benefits,” he says.

Patel adds that his children have a hard time finding jobs and that he was scammed out of a welfare payment he was given by the federal government, but he doesn’t blame the prime minister.

“I don’t care if they give me what they owe me, I will still vote for him,” he tells the BBC.

At 73, Modi remains a hugely popular but equally polarizing figure, both in India and abroad.

His supporters claim he is a strong and efficient leader who has delivered on his promises.

His critics allege that his government has weakened federal institutions and cracked down on dissent and press freedom.

They also accuse him of belittling the Muslim minority in the country, which they say feels threatened under his rule.

“Modi has big admirers and critics. You either like him or you don’t,” explains political analyst Ravindra Reshme.

Opinion polls put Modi comfortably ahead of his rivals, but they have been wrong several times in the past. This time, it seems they were wrong again. Modi did not get the overwhelming endorsement that was expected.

Modi brand

Despite the fact that he will not get the supermajority he had hoped for, Modi is his party’s biggest draw.

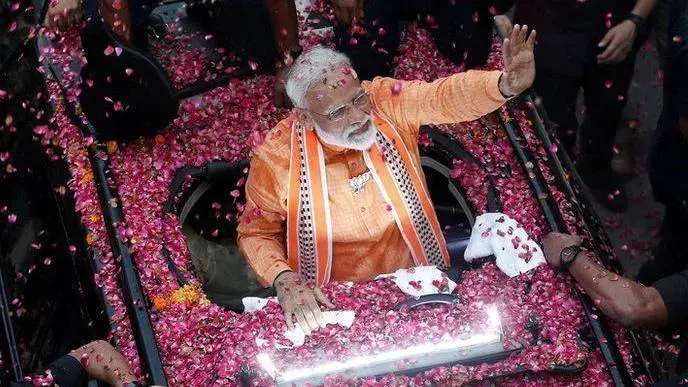

In India, his face can be seen everywhere: on bus shelters, billboards and newspaper ads, and at televised election rallies.

When the country hosted the G20 summit last year, New Delhi was awash with posters of him welcoming world leaders.

The event’s organizer and its chairmanship usually rotate every year, but the ad campaign seemed to show that India had won the presidency thanks to Modi’s efforts.

“Modi turned it into a mega-event. In many ways, he understands what an event is all about and how it should be used,” Santosh Desaim, an expert on advertising campaigns, told the BBC.

Modi and his team have an excellent understanding of what it means to have a brand and to have narrative control.

He is highly visible, but it is rare for journalists or ordinary citizens to be able to ask him tough questions.

Since becoming prime minister he has not held a press conference in India, while the interviews he gives are rare and he is rarely questioned.

RK Upadhya, a political analyst, explains that to become prime minister, Modi had to overcome the media’s portrayal of him as “the one responsible for the Gujarat riots.”

Subsequently, a Supreme Court-appointed panel found no evidence that Modi was complicit in the 2002 violence when he was ruler of the state.

More than 1,000 people died, mostly Muslims.

Upadhya explains that after that he wanted to show the media that he didn’t need them and that he could get the support of the people without their help.

And so he did. Today he is the politician with the most followers on Instagram worldwide and has 97.5 million X followers.

His base isn’t just digital: he also shares his thoughts on a radio show that airs monthly.

Almost all of his public interactions seem carefully choreographed.

Over the past decade, photos have emerged of him inaugurating an immense number of projects, in meetings with his supporters, snorkeling and even meditating in a cave after the 2019 election campaign.

Modi, who never misses an opportunity to connect directly with the people, has reached out to younger Indians and presented awards to popular and influential people.

At a recent event in the state of Kerala, he spoke a couple of sentences in Malayalam, the local language, which drew a huge wave of applause.

Political analyst Sandeep Shastri asserts that there is a lot of symbolism in many of the things that Modi does and that the media broadcasts.

“The place he chooses to spend vacations, the festivals he attends,” Shastri adds.

Foreign visits, including routine ones, are widely broadcast by the national media and celebrated at home.

He gives speeches amid huge congregations abroad led by the diaspora and such images are repeatedly played on national television as evidence of his global popularity.

Divisive politics

But in Varanasi, not everyone is so happy.

Little has changed in recent decades in Lohta, a Muslim-majority neighborhood where we saw drainage and crumbling infrastructure.

Nawab Khan, who lives in Lohta, says weavers like him have become poorer in the last 10 years.

“The only way to prosper is to be a BJP supporter (…) Those who buy sarees have become richer, and those who make them (who are predominantly Muslim) have become poorer,” he alleges.

Dileep Patel, a BJP member, rejects persistent accusations that Muslims are being marginalized or discriminated against by the government.

He assures that welfare schemes are distributed fairly.

He further blames opponents for “scaring our Muslim brothers and sisters” before Modi came to power in 2014.

“Since then, they are not afraid and their confidence in the BJP is increasing day by day,” he continues.

However, in the past 10 years there have been numerous attacks on Muslims by right-wing groups, many of them deadly, and anti-Muslim hate speech has soared.

“When India and Pakistan were divided, our forefathers rejected the call of Muhammad Ali Jinnah (founder of Pakistan) and stayed in this country. We too have given our blood to build this country. However, we are treated as second-class citizens,” says Athar Jamal Lari, who is contesting against Modi in Varanasi.

And in recent weeks, some of that sentiment seemed to resurface in the midst of the BJP campaign. Modi himself has been accused of using divisive and Islamophobic language, especially at election rallies, although he denies it.

Uneven growth

It is not just residents of Lohta, Varanasi’s predominantly Muslim neighborhood, who feel they are getting a raw deal.

Residents in other parts of the prime minister’s constituency are still waiting to see some positive change.

In Chetavani village, just a few kilometers from Kakrahiya, we met dozens of people living in dusty shacks.

“Local officials evicted us from our homes and brought us here. We can’t even get drinking water here,” says 26-year-old Rajinder.

Still, he says he will continue to vote for Modi.

Like Shiv Johri Patel, the sari weaver, many people here live in anger with local officials, but not with the prime minister.

At first glance, Kakrahiya is very different: it has an air of relative prosperity and there is running water.

“Now we have toilets, gas cylinders and houses,” explains Chiraunji, sitting in the kitchen of her half-built house. She says she admires Modi.

She was given a free cooking gas cylinder through a government scheme, but says she can’t fill it often.

According to analysts, one of Modi’s biggest challenges is to generate quality jobs for India’s burgeoning youth population.

A divided opposition

Modi has been helped by the absence of a strong and coherent opposition to challenge him domestically.

When he looked vulnerable, they failed to capitalize on it.

His government has been criticized for its handling of the covid pandemic and the opposition also accuses him of crony capitalism, alleging that he favors a few big business families.

However, his opponents have largely failed to hit their blows, and these controversies do not seem to matter to his many supporters.

“A big part of managing Modi’s image is to make sure that he is never associated with a negative outcome that can be attributed to someone else or other factors,” Sircar notes.

Modi’s supporters praise him because he “never rests.”

His incessant schedules and constant media coverage cement the impression that he is always working.

Shastri claims that when Modi came to power in 2014, the previous government was seen as “ineffective.”

However, Sircar points out that a major challenge facing the BJP is that it relies heavily on a small number of states mainly in northern India.

Modi has been working hard to make gains in the south: in the run-up to the elections, he visited the states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala several times and held large rallies.

But in recent months, the opposition has become more united and consistent in its messaging.

And this seems to have had an impact on the results of a crucial election.