When you arrive at Kabul International Airport, the first thing you notice is the women, dressed in brown scarves and black capes, stamping passports.

The airstrip, which a year ago was the scene of a tide of panicked people desperate to escape, is now much quieter and cleaner. Rows of white Taliban flags flutter in the summer breeze: billboards of the old famous faces have been painted.

What lies beyond this gateway to a country that was upended by a swift takeover by the Taliban?

Leave the work to the men

The messages are amazing, to say the least.

“They want me to give my job to my brother,” writes a woman on a messaging platform.

“We earned our positions with our experience and education. If we accept this, it means that we have betrayed ourselves,” declares another.

I am sitting with some former senior officials from the Ministry of Finance who share her messages.

They are part of a group of more than 60 women, many from the Afghan Revenue Directorate, who joined after being ordered home last August.

They say they were told by Taliban officials to “send resumes to your male relatives who may apply for your jobs.”

“This is my job,” insists a woman who, like all the women in this group, anxiously asks that her identity be hidden. “I fought very hard for over 17 years to get this job and finish my master’s degree. Now we are back to square one.”

In a phone call from outside Afghanistan, we are joined by Amina Ahmady, who was the CEO of this office.

She managed to leave, but that’s not a way out either.

“We are losing our identity,” she laments. “The only place we can keep it is in our own country.”

The title of her group, “Women Leaders of Afghanistan,” gives them strength. What they want is your job.

It was women who took advantage of new opportunities for education and job opportunities during two decades of international commitment that ended the Taliban regime.

Taliban officials say the women continue to work. Those who do it are mainly medical personnel, educators and security workers, even at the airport, in spaces frequented by women.

The Taliban also stress that women, who once held around a quarter of government jobs, still get paid, albeit a small fraction of their salary.

A former official tells me how a Taliban guard stopped her in the street and criticized her Islamic veil, or hijab, even though she was completely covered.

“You have bigger problems to solve than hijab,” she replied, another moment of women’s determination to fight for their rights within Islam.

The risk of famine

The scene seems idyllic. Sheaves of golden wheat shimmer in the summer sun in the remote central highlands of Afghanistan. A soft mooing of cows can be heard.

Noor Mohammad, 18, and Ahmad, 25, continue to brandish their sickles to clean up a piece of remaining grain.

“This year there is much less wheat because of the drought,” Noor says, sweat and dirt on his young face. “But it’s the only job I could find.”

A harvested field stretches into the distance behind us. It’s been 10 days of backbreaking work by two men in the prime of their lives for the equivalent of $2 a day.

“I was studying electrical engineering but had to drop out to support my family,” she explains. His regret is palpable.

Ahmad’s story is just as painful. “I sold my motorcycle to go to Iran but I couldn’t find a job,” he explains.

Temporary employment in neighboring Iran used to be an answer for residents of one of Afghanistan’s poorest provinces. But work has also slowed in Iran.

“We welcome our Taliban brothers,” says Noor. “But we need a government that gives us opportunities.”

Earlier in the day, we sat around a gleaming pine table with Ghor’s provincial cabinet, men in turbans positioned alongside Taliban governor Ahmad Shah Din Dost, who was shadow deputy governor during the war.

“All of these problems make me sad,” he says, listing the poverty, bad roads, lack of access to hospitals and malfunctioning schools.

The end of the war means that more aid agencies are now working here, including in districts that were previously off limits. Earlier this year, famine conditions were detected in two of the most distant districts of Ghor.

But the war is not over for Governor Din Dost. He says that he was imprisoned and tortured by US forces. “Don’t give us more pain,” he asserts. “We don’t need help from the West.”

“Why does the West always interfere?” he asks. “We don’t question how they treat their women and men.”

In the days that followed, we visited a school and a malnutrition clinic, accompanied by members of his team.

“Afghanistan needs attention,” says Abdul Satar Mafaq, the Taliban’s young college-educated health director, who appears to be more pragmatic. “We have to save people’s lives and it doesn’t need to involve politics.”

I remember what Noor Mohammad told me in the wheat field. “Poverty and hunger is also a struggle and it’s bigger than the shootings.”

Taliban Governor Ahmad Shah Din Dost.

The closure of schools for girls

Sohaila, 18, is excited.

I follow her down some dark stairs to the basement of the women-only market in Herat, the ancient Western city long known for its more open culture, its science, and her creativity.

It is the first day that she opens this bazaar: the Taliban closed it last year, and it was closed by the covid-19 pandemic the year before.

We peer through the glass front of her family’s clothing store, which isn’t ready yet. A row of sewing machines stands in the corner, red heart balloons hang from the ceiling.

“A decade ago, my sister opened this store when she was 18,” Sohaila tells me, sharing a condensed story of her mother and grandmother’s sewing of brightly patterned traditional Kuchi dresses.

Her sister had also opened an internet club and a restaurant.

The premises are dimly lit, but in this gloom there is a ray of light for women who have spent too much time sitting at home.

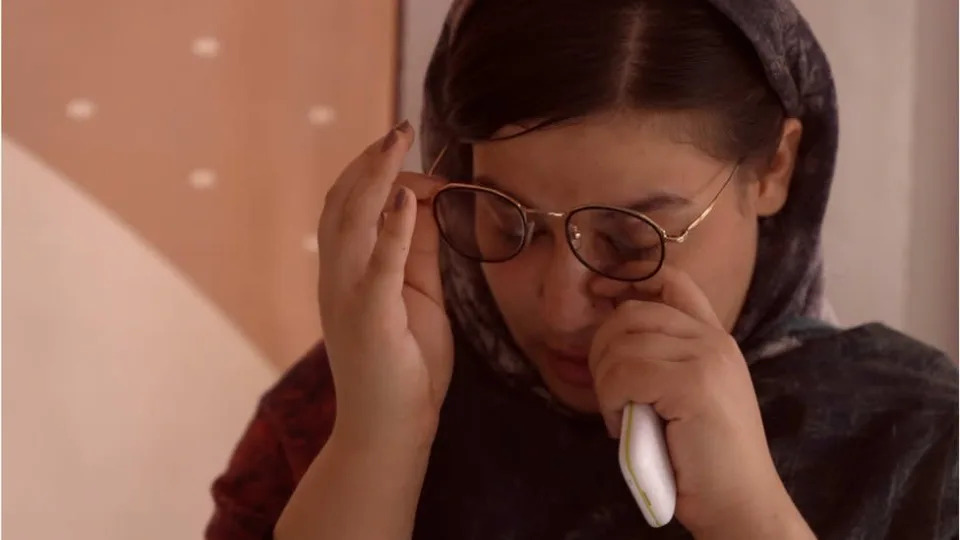

Sohaila has another story to share.

“The Taliban have closed down high schools,” she says matter-of-factly about something that has huge consequences for ambitious teenagers like her.

Most high schools are closed on orders from the Taliban’s ultra-conservative top clerics, even though many Afghans, including Taliban members, have called for them to be reopened.

“I’m in the 12th grade. If I don’t graduate, I can’t go to college.”

I ask her if she can be the Sohaila she wants to be in Afghanistan. “Of course,” she declares confidently. “It’s my country and I don’t want to go to another.”

But a year without school must have been tough. “It’s not just me, it’s all the girls in Afghanistan,” she comments stoically.

“It’s a sad memory,” she says.

Her voice trails off as she breaks down crying.

“I was the best student.”