Whitney Houston’s tragic downfall: drugs, scandals with her husband and her death by drowning in the bathtub.

It was a slow decline that lasted two decades. Addictions and scandalous fights with her husband Bobby Brown undermined her health and her gifts as a singer. Her last moments and the discovery, in her bedroom, of the cause of her death in 2012. Today would have been her 60th birthday

A Los Angeles nightclub. Darkness, just over thirty people and cigarette smoke forming blue clouds between the ceiling and the tables. On stage a good gospel singer who had had no luck in making the leap to pop. At the tables they are more concerned with their business than with what is going on up there: conquests, some marital quarrel, business deals that are closed in front of a glass of whiskey. A teenage girl leaves the back of the stage, the place of the backing singers, and takes a few steps to the front when the singer, her mother, invites her to sing. She takes the microphone and accompanied by a not too emphatic piano starts with Greatest Love Of All, a song composed several years before for the Muhammad Ali biopic that starred himself and that George Benson had placed in the top 10 of the R&B chart.

No one present remembered the song which, at the time, had gone largely unnoticed. Except for a man sitting, deliberately, at one of the last tables; he wanted the lack of light to protect him. What the teenager didn’t know was that this man was the one who had commissioned, a decade earlier, the song for the film’s soundtrack. The original version of the song sounded like a good Stevie Wonder ballad (which, you know, is high praise). The young woman recaptured it and took it to unimaginable heights. Her voice at the forefront, the passion of her 20s and an ancestral wisdom that seemed to accompany her on stage and inhabit her vocal cords.

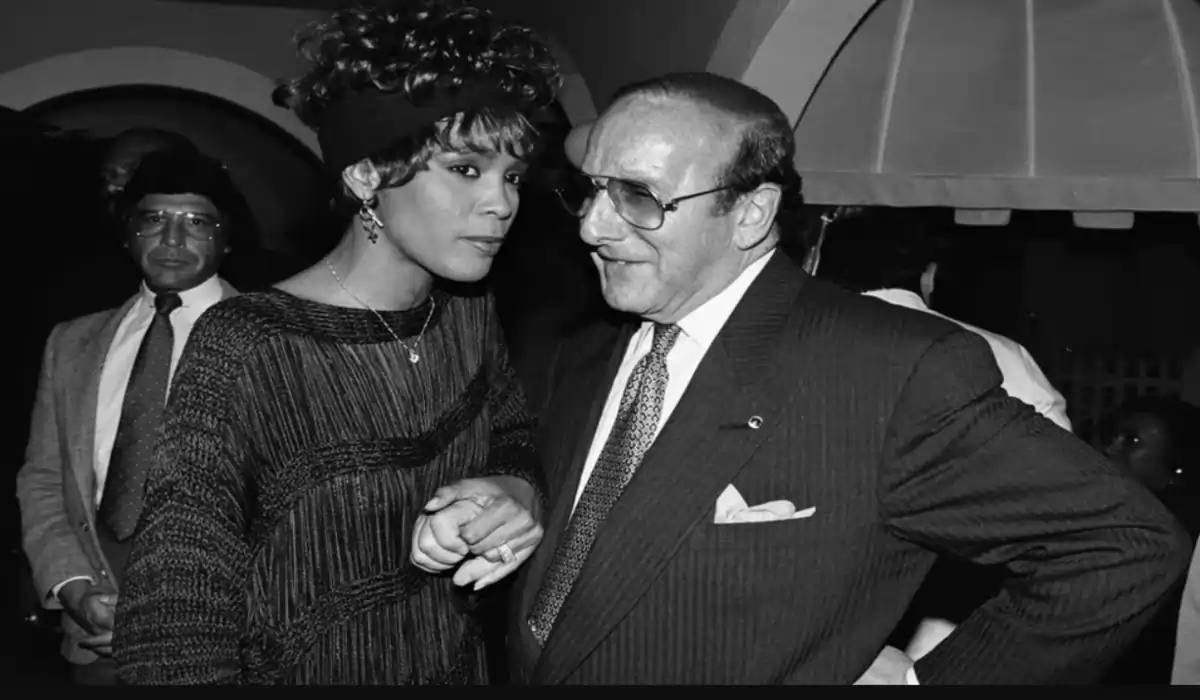

As soon as he heard the first verse, the man, Clive Davis, pope of the music industry, knew he had a new gem for his exclusive catalog of discoveries that included Bruce Springsteen, Janis Joplin, Santana and Aerosmith, among others. He knew this girl had a gift, a unique talent. He knew, of course, that Whitney Houston would be a star. That same night, in the cramped club dressing room, he had her sign a contract with Arista Records, his record label.

Clive Davis didn’t have to wait for the first album to come out to see his success. He was invited to one of the most watched programs on American television, The Merv Griffin Show. He accepted on one condition: that once the interview was over, the musical number (usual every night) would be his new artist, the 20-year-old girl who was recording her first album.

That night Whitney Houston appeared for the first time on television. She was bare-chested, wearing a metallic blue jacket, baggy black pants, afro hair, short and tight. As soon as the camera focuses on her, she starts singing. Her voice is subdued, the volume is low, almost shy, her hands in front of her chest, clasped. The song is Home, from the film version of the Wizard of Oz with Liza Minelli and Michael Jackson. But after the first verses the miracle happens: the young woman forgets the frame, the millions of people watching her at home, the cameras. Her voice is projected, she lets loose and in the studio and in every home they witness the birth of a singing diva. The performance is memorable. One of the greatest debuts in history.

Rise, Triumph, and Tragic Decline: The Spectacular Career and Heartbreaking Demise of Whitney Houston

Whitney Houston was one of the pop queens of the 80s. Her rivals in those years were heavyweights. Madonna, Prince, Michael Jackson. But this girl with her first two albums swept the records. Her voice was prodigious, a perfect natural instrument. But she was much more than that. She seemed to know everything. The training she had received from her mother had been effective. She had stage presence, sympathy, she danced. To her (over) natural gift she added a refined technique. It was not a wild talent. She could hit any note and hold it for as long as necessary. He was the crossover that the market and the public were waiting for. There was the feeling of soul, the strength of R&B, the lightness and joy of pop.

As soon as she appeared, the specialists placed her in the big leagues, with the incomparable interpreters. Sinatra, Aretha Franklin, Ella Fitzgerald. Whitney Houston, with her magnetic voice, played in that league, the Justice League.

Her emergence was dazzling. Her first album reached number one in the charts and she was the first female singer to have seven consecutive number one singles in the Billboard chart: Saving all my love for you, How will I know, Greatest love of all, I’m gonna dance with somebody, Didn’t we almost have it all, So emotional, Where do broken hearts go. An impeccable and astonishing sequence.

There were other hits. And the arrival of the cinema. The box office success and the craze caused by her version of I Will Always Love You, which broke sales and chart-topping records.

Then came the fall. Terrible, constant, painful and public. Whitney and her talent (or her genius) were falling apart in the public eye. Marital problems, drug addiction, bad decisions. And an untimely but predictable death at age 48.

When an artist dies, fans express their grief on social networks. Those who have already made their career, those who are defeated only by the years and by old age, are dismissed with the gratitude of the company and the emotion that their creations provided for decades. Those who die earlier, those who do not reach old age provoke another kind of pain. The pain of the unfinished, pain increased by the feeling of unfinished work, that they still had much to give, that they lost songs, books or movies that will never be again, that only they could put into the world. The feeling is of irreparable loss, that what did not happen, no one will be able to create it. With Whitney, even though she died very young, at the age of 48, that did not happen. There was the conviction that she no longer had anything to give, that her gift had dissolved in the tangle of drugs and idleness, that she had given up a long time ago.

It had been two decades since her artistic career had known the success that had accompanied her in her early years. Her downfall, predictable, public and often morbidly accompanied by the press and the public, had lasted two painful decades.

Her mother was Cissy Houston, a gospel singer of exquisite technique, with experience in the world of soul, she had done backing vocals for Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight and other divas of black music. Her cousin was Dionne Warwick. And her godmothers were none other than Aretha Franklin and Darlene Love.

In one of the first television interviews, the show’s host after listing all these family connections, asked Whitney, “And who’s your grandfather, Duke Ellington?”

But Whitney was much more than this perfect lineage. She had sung in her church from a very young age, had accompanied her mother on many of her performances, and had even filled in for her on occasion. Cissy Houston wanted her daughter to finish school before embarking on an artistic career. After leaving school Whitney began performing in small nightclubs. Word spread fast and talent scouts began to follow her night after night. Until Clive Davis came along.

Her mother’s show business experience kept them from rushing in. Cissy, demanding, wanted for her daughter all the success that she could not live (success in that world is lived, it is inscribed in the body).

After the first two albums it seemed that everything she sang turned to gold. Before the 1991 Super Bowl she performed Star Spangled Banner, the American anthem. It was a stirring performance. The version was released as a single and reached the top 20.

The following year he ventured into film for the first time. The Bodyguard would become a global success that, believe it or not, far surpassed what he had achieved with his first albums.

The film is not much. Just a conventional story starring two strong figures like Whitney and Kevin Costner. The interracial love story in the mainstream, the final kiss with a last minute descent from the plane have their impact. But the breaking point is the film’s theme song. An old Dolly Parton country song that Costner suggested when he found out that the originally chosen song, What Becomes of the Broken Hearted, a cover of a great soul ballad sung by Jimmy Ruffin had been selected as the main theme for the film Fried Green Tomatoes.

The actor is also credited with the best musical production decision of the early nineties: the absence of production, machines and accompaniment. The soundtrack’s producer, David Foster, thought it was a lousy idea and commercial suicide. “What radio would pass a song where the first 45 seconds are a cappella?” he argued with some logic. Costner and Houston, however, insisted. He barely had to sing just once for Foster and everyone in the studio to assume that the only possible version of the song was that one. The perfect voice, naked, up front, with all the technical expertise enhancing it.

The song and the album broke sales records. It was a huge global hit. It was Whitney’s last big hit.

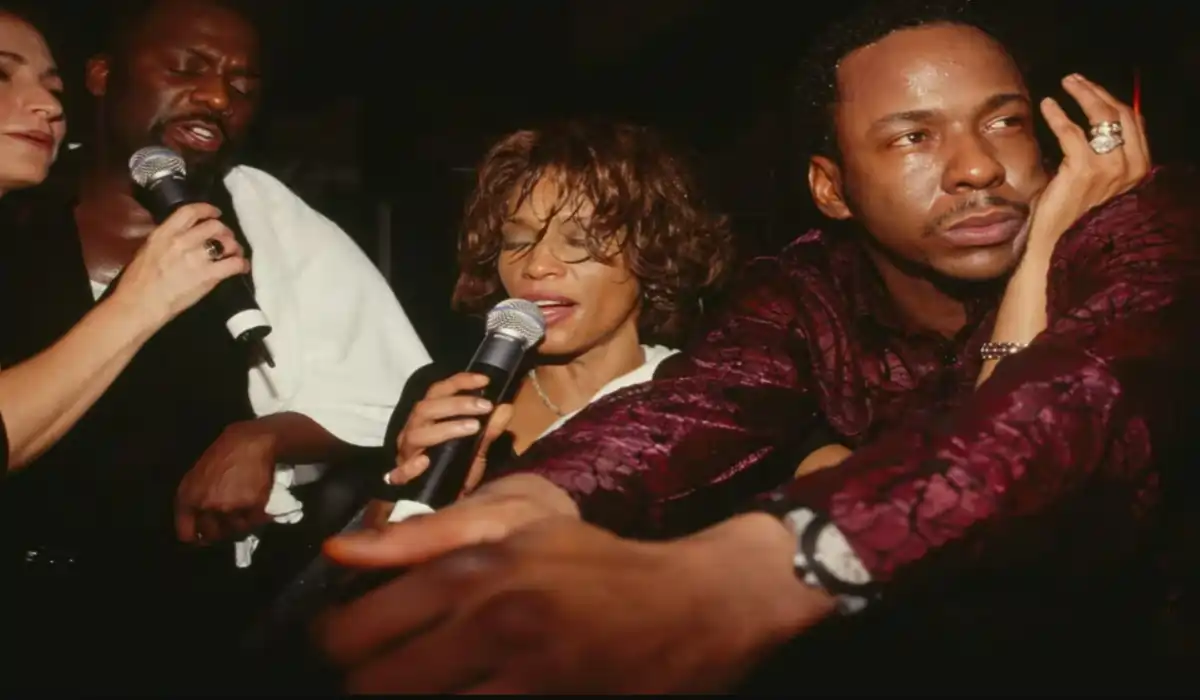

At the 1989 Soul Train Awards she met her future husband, singer Bobby Brown. Former member of New Edition, Brown had great success as a soloist at that time with his song My prerogative. Bad boy, provocative, somewhat foul. From that night on, they would not separate for years. The relationship was stormy and both ended up lost in drugs and permanent fights. The artistic careers of both never knew splendor again.

Many blame Whitney’s downfall on Bobby Brown. Others blame her mother and the dull competition between the two. Also on the list of alleged causes: the departure of Clive Davis from Arista, bad company, a father with the soul of a gigolo, a sexual abuse suffered at the hands of her cousin Dee Dee Warwick or the closeness of Robyn Crawford.

The causes, culprits and justifications pile up. What is certain is that those 20 years of excesses, drug dependency, roles, non-compliance and flirtation with misfortune belong to Whitney.

Whitney Houston with Clive Davis, her mentor. Davis signed her to a contract as soon as he heard her sing. (Photo by Lester Cohen/Getty Images)

Whitney became a regular on the front pages of the tabloids. The fights with Bobby Brown, his arrests and infidelities, the erratic shows, the suspended performances, the mediocre albums, the defiant TV interviews, the voice that loses luster and fades away.

In the midst of that mess of screams, family violence, insanity and drugs, Bobbi Kristina, the couple’s daughter, was growing up. She also had a tragic end and, due to her age, much more terrible. Bobbi Kristina, at the age of 22, was found unconscious in the bathtub of her home with a drug overdose. So was her mother. She died in 2015 after six months in a coma. There is one more link in this tragic story. On New Year’s Day 2020 Nick Gordon, Whitney’s heart child and Bobbi’s boyfriend for many years, died of an overdose.

It was as if the young men were mountain climbers attached to another who, above them, was guiding the climb up the steep slope; as the one in front took off, it was inevitable that shortly thereafter he would drag those below him.

Whitney’s erratic behavior in his last long years had millions of witnesses. She had to cancel appearances at the Oscars, Clive Davis’ Rock Hall of Fame induction and dozens of concerts. Some tabloid took a chilling photo of the star’s bathroom on its cover: crumbling, with drug residue on various plates, dirt and neglect in every corner.

During the recording of the soundtrack of Waiting to exhale she had to be urgently hospitalized for an overdose. Several rehabilitation treatments failed. She boasted to journalist Dianne Sawyer that she didn’t do crack because it was “a poor man’s thing”.

The machinery tried to keep working. They organized tours for her that she couldn’t do. Shows where her condition was pitiful and her voice seemed to be gone forever, a sad, hoarse croak, listless and out of tune. As if it were a sad parody of what had been.

Sunset of February 12, 2012. Beverly Hills Hotel. Eve of the Grammy Awards. A woman, Whitney’s assistant, enters the room. She had not been able to reach her by phone for some time. When she opened the door, she was startled by the silence. She tried to fool herself, she tried, in that brief second, to believe that the singer was taking a late nap.

As soon as she felt the water burning her ankles and calves as she entered the living room, she knew it was finally over. She did not feel anguish, nor did she despair. A bitter resignation ran through her body, a dull ache.

As she walked to the bathroom – from where the water was coming from and already reached ten centimeters above the carpet – she thought she was living a déjà vu. Only this had never happened before, at least not with such irreversible consequences. But every night, when the star left her care, the assistant imagined that her next working day would be like this one.

Bobbi Kristina, daughter of Whitney, and Nick Gordon, Bobbi’s boyfriend and kind of adoptive son of the singer, died very young from an overdose. The family tragedy did not end with Whitney (Photo by Frazer Harrison / GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA / AFP)

As she opened the bathroom door, a small wave of boiling water splashed up to the edge of her thighs.

In the overflowing Jacuzzi, face down, floated the naked body of Whitney Houston. Lifeless.

The assistant called, without desperation, without raising her voice, barely with a few choking tears, to the hotel reception. She said it was an emergency. She hesitated between asking for the police or an ambulance. “Come quickly, please,” he asked. “I think Whitney Houston is dead.”

When paramedics and police went up to the fourth-floor bedroom where the singing star was staying, they found traces, in every square meter of the apartment, that made it unnecessary to wait for the autopsy and toxicology report to find out what the causes of death were.

A plate with a white powdery substance, marijuana, a burnt spoon with traces that seemed to have been methamphetamines, two dozen bottles with legal medicines (painkillers, muscle relaxants, Xanax and others).

Today Whitney Houston would have been 60 years old.