In addition to Donald Trump, other U.S. presidents faced trouble with the law with charges ranging from speeding to corruption.

Donald Trump has made history so many times. The first president with neither government nor military experience. The first to be impeached twice. The first to vigorously challenge his successor’s certification to the White House. Now he adds another debut: Even as he hopes to return to the White House in 2025, he is the first former president to be impeached.

However, Donald Trump is hardly the first U.S. president or former president to face trouble with the law.

The most recent line Trump crosses again challenges the aura of the American presidency, nurtured on the infallibility of George Washington but humanized time and again, through scandals born of greed, abuse of power, corruption, naiveté, sex and lies about extramarital affairs.

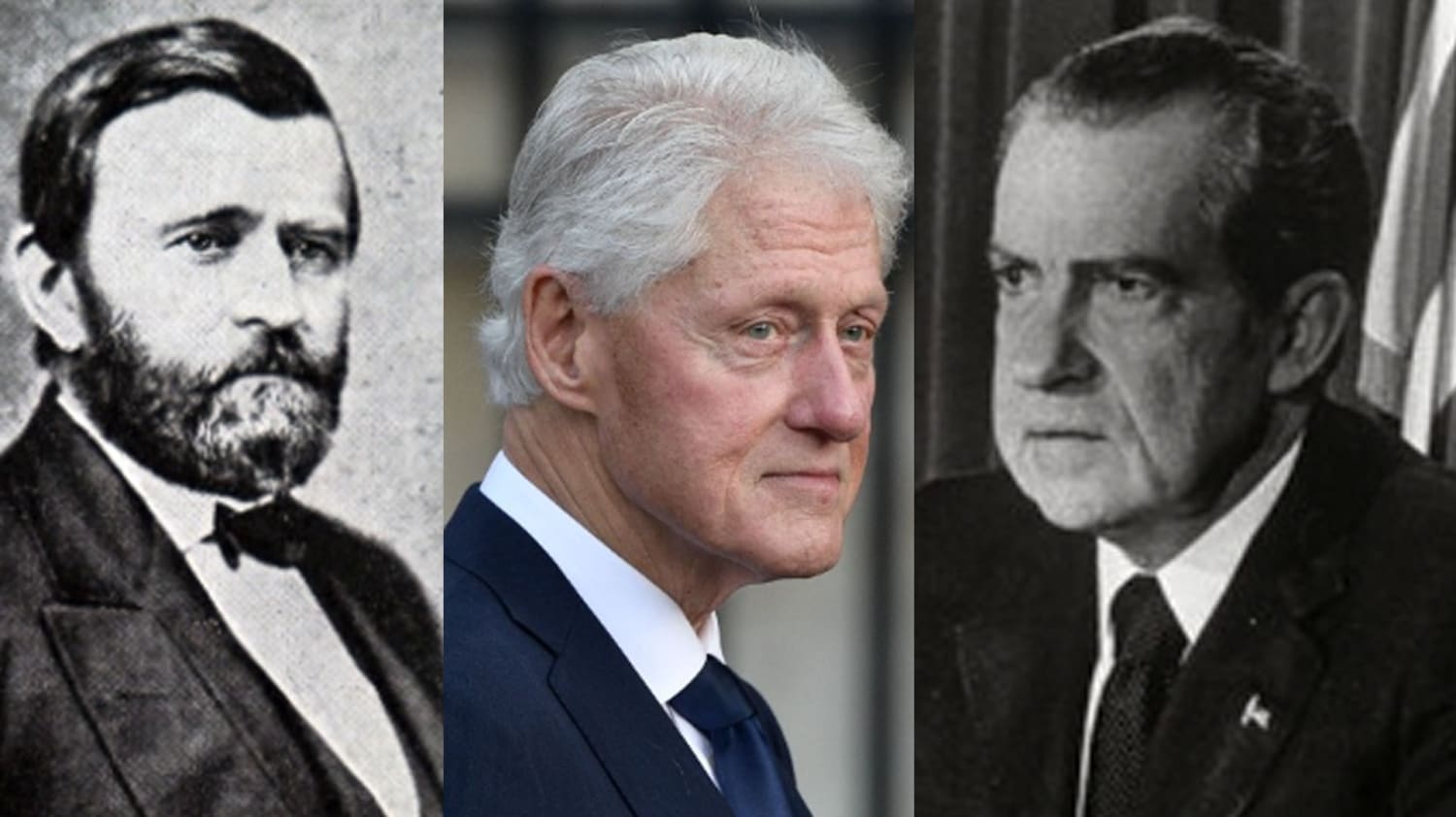

In 1974, Richard Nixon may well have avoided criminal charges of obstruction of justice or bribery, related to the Watergate scandal, only because President Gerald Ford pardoned him a few weeks after Nixon resigned the presidency.

Bill Clinton had his law license suspended for five years in his native Arkansas after he reached a plea deal with prosecutors in 2001, at the end of his second term, over allegations that he lied under oath about his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

Some historians wonder about the fate of President Warren Harding had he not died in office, in 1923. Numerous officials around him would have been implicated in various crimes, including his Secretary of the Interior, Albert B. Fall, whose corrupt land transactions became known as the “Teapot Dome scandal.”

The walls were closing in around him,” presidential historian Douglas Brinkley said of Harding. In the United States, the secretary of the Interior is a position that corresponds to that of director of the Department of Natural Resources in other countries.

According to reports, Trump’s indictment in New York relates to how certain business records were falsified in connection with a $130,000 payment to porn actress Stormy Daniels in 2016, shortly before Trump defeated Democrat Hillary Clinton for president, to prevent Daniels from going public about a sexual encounter she said she had had with him years earlier. Trump denies having sex with her.

Trump is also under investigation for allegedly trying to change the results of the 2020 vote in Georgia, a state he lost narrowly to Democrat Joe Biden, and for his role in a violent mob assault on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, when Trump supporters tried to prevent Congress from certifying Biden as president. Trump has denied wrongdoing and has called the New York investigation a “witch hunt.”

While in office, Trump adopted a Justice Department judicial opinion that a president could not be impeached. However, once a president leaves office, that protection disappears.

Most former U.S. presidents over the past half-century have led relatively quiet public lives: they created foundations, gave lucrative speeches or, in the case of Jimmy Carter, did plenty of charitable work. A fall from grace marked Nixon for years, though he eventually resurfaced to speak on global issues and advise aspiring politicians and potential presidents, including Trump.

The immediate cause of Nixon’s resignation was the discovery of the “smoking gun”: tape recordings from the Oval Office, initiated by Nixon himself, which revealed that he had ordered a cover-up of the 1972 illegal break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington.

By 1974, the scandal had expanded far beyond the initial crime.

Many of Nixon’s top aides had resigned and were eventually jailed. Nixon himself was a possible target of the special prosecutor appointed to the Watergate case.

There were partisan people in Congress and on the special prosecutor’s team who would have liked to have seen Nixon indicted after his resignation, or who at least believed the pardon was premature,” says John A. Farrell, author of ‘Richard Nixon: The Life,’ an award-winning biography published in 2017.

“But the special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, had consistently chosen to deal with respect to Nixon through the constitutional, impeachment process.”

Farrell notes that Ford so quickly pardoned Nixon after his resignation that Jaworski’s office did not have time to fully consider the charges against Nixon. Ford himself later said that an “indictment, trial, conviction and whatever else happened” would have distracted the country from more immediate problems.

“Here’s what you can tell: Nixon himself was very concerned about the possibility (of impeachment), to the point that it would impair his health,” Farrell said, referring to Nixon’s problems with his phlebitis: inflammation of the veins in his leg.

He reflected aloud on how some of history’s great political writings had been crafted in prison cells. His family, deeply concerned, contacted the White House, alerting Ford’s aides to the deteriorating condition of the former president.”

The Nixon and Harding administrations were among several defined by the scandal, without the president being formally charged.

Ulysses Grant, the Union general and Civil War hero, was otherwise naive about those around him. Numerous members of his presidential cabinet were involved in financial crimes, from extortion to market manipulation. Grant himself was caught for a more trivial offense.

During his first term, in 1872, he was stopped twice for speeding in his carriage.

The second time Grant had to pay a $20 fine, but he never spent a night in jail,” recounts historian Ron Chernow, whose biography of Grant was published in 2017.

A tragedy may have saved a future president.

In the fall of 1963, Vice President Lyndon Johnson had fallen from grace in the John F. Kennedy administration and was in possible jeopardy with the law because his top aide, Bobby Baker, was under investigation for financial dealings and influence peddling. Johnson, with a history of questionable finances of his own, denied any close ties to a man he once claimed to love like a son.

On the morning of November 22, 1963, Life magazine was mounting an investigation and congressional hearings had just begun. Within hours, however, Kennedy had been assassinated, Johnson had been sworn in as his successor, and interest in Baker’s affairs essentially ceased.