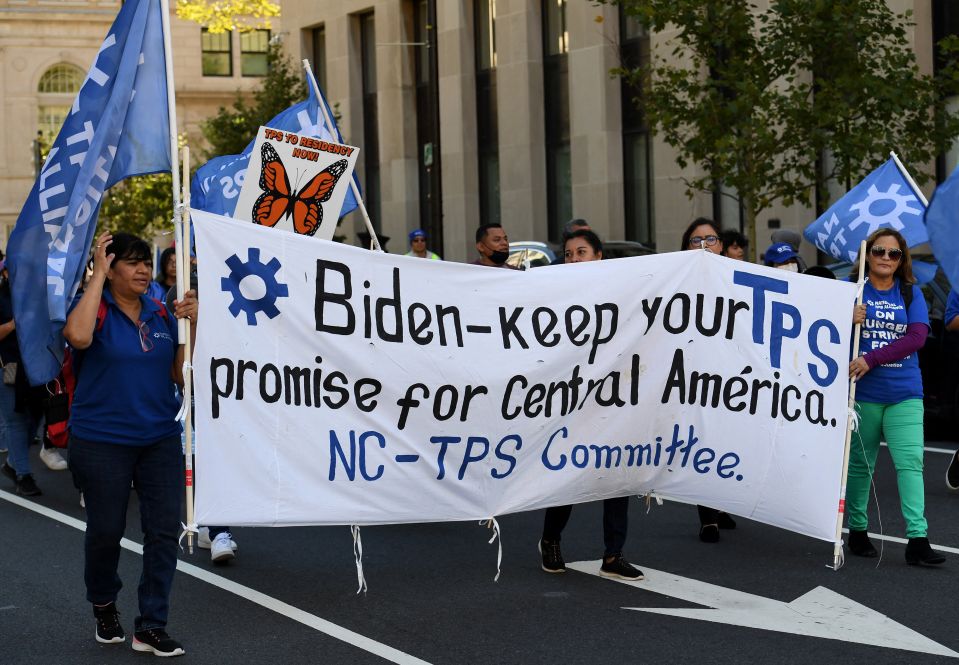

Beneficiaries of temporary protected status (TPS) could lose their protection at the end of the year and 250,000 are at risk of being deported to their countries of origin.

After more than a year of negotiations, settlement talks between the Biden administration and the plaintiffs over temporary protected status broke down Tuesday, leaving more than 250,000 people at risk of deportation.

The litigation followed concerted actions by the Trump administration to end TPS for citizens of several countries — El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti, Sudan, and Nepal — as part of its efforts to reduce long-term use of the protections, according to The Los Angeles Times published.

TPS is a form of humanitarian aid given to countries devastated by natural disasters or war and allows recipients to legally work while staying in the US Created in 1990, the program currently applies to people from 15 countries.

The plaintiffs obtained temporary relief in 2018 when a federal district judge in San Francisco granted an injunction to block the termination of the protections.

But in 2020, a three-judge panel at the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco reversed the order in a 2-1 decision.

This resolution has not become effective, because the immigrants’ lawyers requested a hearing before the full court, which is still pending.

The Biden administration redesigned temporary protected status for Haiti and Sudan, but has not done so for the other four countries.

Those beneficiaries could lose their protections later this year as the Biden administration goes to court to defend decisions made in the previous administration.

Despite the fact that, as a presidential candidate, Joe Biden called President Trump’s decision to rescind TPS “a recipe for disaster,” promising to protect beneficiaries from being returned to unsafe countries.

Emi MacLean, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, said a settlement would have provided security for TPS holders who have felt vulnerable during the past four years of litigation.

“There’s a reason people are losing faith in the Biden administration),” she said. “These actions leave us very concerned as to whether they recognize the urgency of this problem and the fact that many lives are in danger due to their unwillingness to act.”

A spokesman for the Department of Homeland Security declined to comment on the pending litigation, but said “current TPS holders from El Salvador, Nepal, Nicaragua and Honduras will continue to be protected for months to come.”

TPS holders and their US citizen children challenged a class action lawsuit in 2018 alleging that government officials had a political agenda in deciding to end protections for those countries and were motivated by racism.

Trump administration officials responded by saying the program was never intended to provide a long-term reprieve.

Plaintiff Elsy Flores Ayala said she was frustrated that a settlement could not be negotiated.

Flores Ayala, 43, her husband, and her 24-year-old daughter have had TPS since 2001, a year after they came to the US from El Salvador.

El Salvador was first designated for TPS in March 2001 after two earthquakes struck the country, killing more than 1,000 people and displacing more than 1 million.

Since then, the US government has cited subsequent natural disasters and gang-related insecurity in redesigns of that policy. Almost 200,000 Salvadorans have TPS, many of them in California.

Flores Ayala said that she and her family, who live in Washington, depend on TPS benefits: she works in child care, her husband does maintenance on an apartment building, and her daughter is in the college. She is also concerned about what could happen if they lose their deportation protections. Her two youngest children, ages 17 and 21, were born in the United States and she fears being separated from them.

“The concern is significant because we don’t know what will happen to us,” she said.

In the 2018 ruling, US District Judge Edward Chen blocked the terminations, saying the recipients risked being uprooted from their homes, jobs and communities.

“They face expulsion to countries with which their children and family members may have little or no ties and which may not be safe,” he wrote.

“Those with US citizen children will be faced with the dilemma of bringing their children with them, giving up their children’s life in the United States (for many, the only life they know), or being separated from their children.”

The judge, appointed by President Obama, also cited Trump’s comments about Haitian and African immigrants coming from “shithole countries,” noting that “circumstantial evidence that race is a motivating factor.”