If you were born between 1980 and 1990, you may remember the Abercrombie & Fitch stores that were so popular with upper-middle-class youth. Venues with loud music, walls with black and white photos of half-naked boys and the famous Fierce cologne in the air.

The clothing chain was one of the most valued among young people, with its black and white and its characteristic aromas of the first decade of the 2000s. However, as a new Netflix documentary reveals , the “back room” of this empire of retail kept secrets of racism, discrimination and bad leadership.

Abercrombie & Fitch, the king of the 2000s

Although the firm’s heyday was in the 1980s and 1990s, Abercrombie & Fitch actually emerged in 1892 as a product line to go on an excursion. In 1988 the Limited Brands company bought the brand and redefined it as a luxury clothing line under the direction of CEO Mike Jeffries.

Teenagers walking into Abercrombie & Fitch stores were greeted by salespeople with athletic bodies who sold them shirts, pants, and everything else needed to look like a high-class youth or with the “frat-boy ” aesthetic .

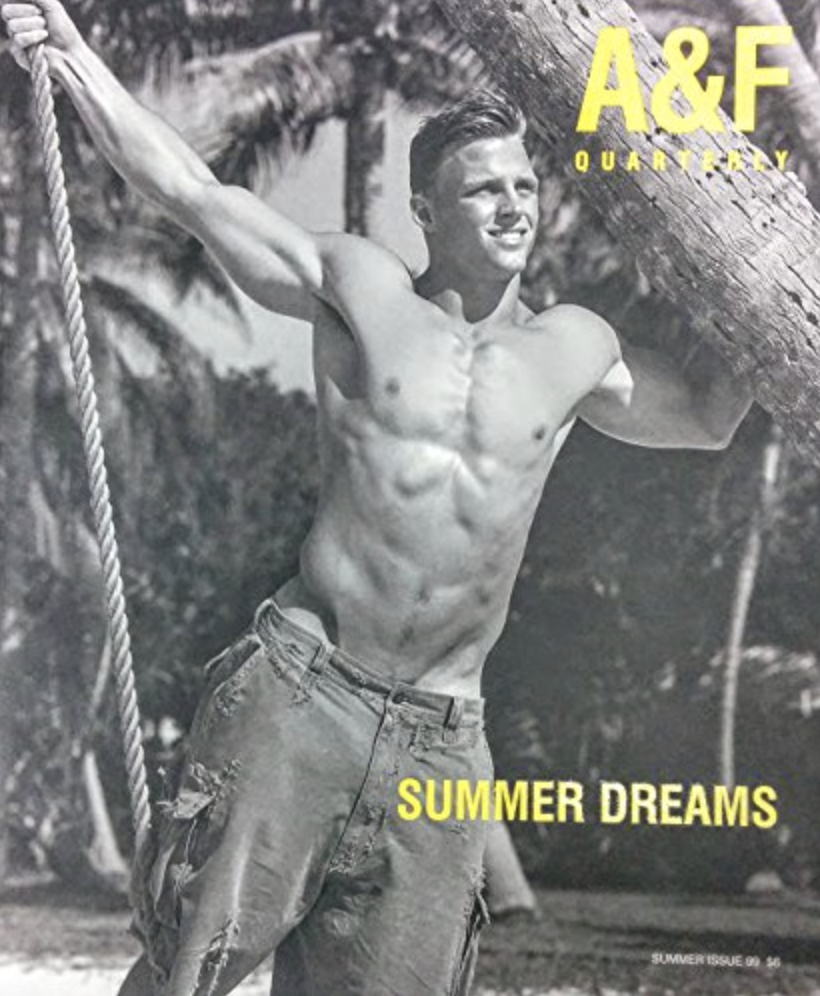

Jeffries, who took over the management in 1992, carefully crafted an image for the brand so that it would be seen as the clothes only “the cool kids” wore. The A&F aesthetic was created by photographer Bruce Weber, famous for his Calvin Klein work. His work portrayed the idealized image of bare-chested American boys engaged in physical activities such as fieldwork.

The CEO’s strategy worked as it repositioned the brand as sexy to young people and propelled the brand’s earnings to $335 million in just three years.

The new look was so successful that Limited Brands launched Abercrombie & Fitch on the New York Stock Exchange in 1996, selling $112 million in its Initial Public Offering (IPO) at $16 a share in a single day.

In 1998 A&F became an independent company from Limited Brands. By 2000, the new company owned brands like Abercrombie Kids and Hollister.

In this way, Abercrombie positioned itself as the most popular retail brand among middle and upper class youth in 2001. Its success was such that the company was valued at one billion dollars.

But soon scandals of racism, hypersexualization of young people and discrimination led to the fall of the brand.

Accusations of discrimination and racism at A&F

The Netflix documentary called White Hot (Burning white in Spanish) shows the discrimination and racism that was experienced in the stores and marketing of Abercrombie & Fitch. Various testimonies reveal that the people who were hired for the front of the stores had to be attractive and preferably white.

According to a company manual , recruiters for store floor staff were required to choose people with “neat, well-cut hairdos,” “pretty and slim,” and whose expressions of culture or race such as dreadlocks were “unacceptable.”

In 2003, nine former employees of the brand sued her for racial discrimination for being fired or relegated to backroom work for not being white. Abercrombie & Fitch ended up settling the dispute with a $50 million private settlement.

Jeffries launched the A&F Quarterly magazine , which ran from 1997 to the end of 2003 . It was a highly criticized publication for its high content of half-naked young people and articles about sex.

Abercrombie was also involved in a scandal for selling thongs in children’s clothing with the phrases “Eye Candy” and “Wink Wink” .

On the other hand, the logos and phrases that had made Abercrombie & Fitch t-shirts famous in their best moments were beginning to be rejected for their racist messages. One of the more infamous t-shirts read “Two wongs can make it white” in reference to Asian laundromat workers. Another example was the shirt that said “Juan more for the road” (Juan más para el camino), which was offensive to the Latino community.

Mike Jeffries wanted only “pretty people” to wear his clothes

In 2012, an interview Mike Jeffries had with Salon magazine resurfaced in which he accepted that he only wanted “pretty, skinny” people to wear his clothes.

“Many people do not belong in our clothes and cannot belong. Are we exclusive? Absolutely. Attractive people attract other attractive people, and we want to market attractive and cool people. We don’t sell to anyone other than that.”

Jeffries noted that his company only hired beautiful people in its stores because “pretty people attract pretty people” to shop.

At the time the CEO apologized saying that the words “had been taken out of context”. However, the comments caused the brand’s earnings to drop more than 10% for 3 years in a row.

These controversies coincided with a change in the mindset of the buyer who began to lose interest in the brand. By 2010 it was already outside or in the last place of the Top 10 retail stores preferred by adolescents.

By the end of 2013, the company had closed 220 stores in three years and announced the closure of up to 130 locations by 2015.

From that point on, the brand started losing money in sales and in its share price and was unable to recover. Yet Jeffries refused to step down from his post as CEO, even when Bloomberg named him in 2013 as “Worst CEO” of the year.

Finally, Jeffries left the company in 2014, when Abercrombie & Fitch had lost 40% of its value.

Abercrombie & Fitch: What the Netflix Documentary Didn’t Say

Jeffries’ story and his mistakes running Abercrombie & Fitch have returned to the public conversation thanks to the Netflix documentary. However, the show doesn’t talk much about what happened to the network afterwards.

The day Mark Jeffries announced his departure , A&F stock jumped 8% almost immediately.

Fran Horowitz, the company’s new CEO, came up with a four-pillar plan to reposition Abercrombie & Fitch’s image. This action plan focuses on redesigning stores, boosting e-commerce, improving the customer experience, and optimizing marketing spend.

It seems that the brand is giving way to a new stage. Currently their marketing strategy is no longer focused on scantily clad models. On the contrary, it has a strong sense of inclusivity and focuses on online sales to attract the precious Generation Z.